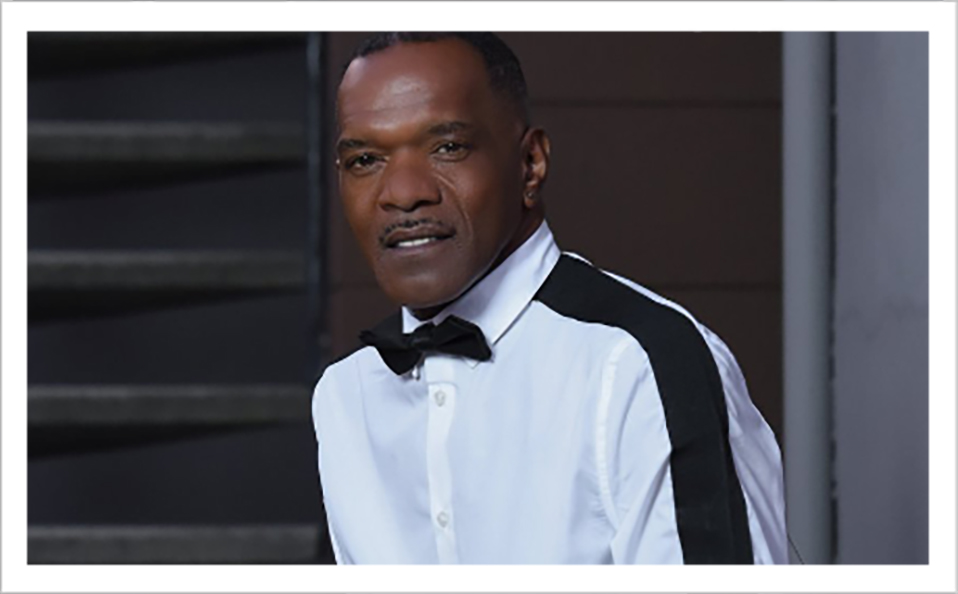

Jesse Brooks

Jesse Brooks is one of the San Francisco Bay Area’s most well–known AIDS activists. The popular photographer and journalist has appeared on numerous anti-HIV stigma campaigns, documentaries, public speaking engagements, and serves as a Health Reporter for the Post Newsgroup. Having overcome years of addiction, and struggles with internalized homophobia and self–hate, he now uses his artistic platform to mobilize Black LGBTQ communities near and far.

Jesse was born in Los Angeles, CA, and moved to Oakland when he was 8 years old. After graduating from Oakland Technical high school, Jesse began exploring his attraction to men. The tragic murder of his partner of seven years sent Jesse looking for ways to cope. Not out, and lacking a social support system, he turned to alcohol and drugs. As his drug use caused problems in a new relationship several years later, his partner became ill. However, he never shared why he was sick because of stigma. Jesse recalled his partner asking questions like, “I wonder if I have AIDS?” and, on a different occasion, “If I had AIDS would you still be with me?” Looking back, Jesse says these were signs that his partner was trying to tell him that he was HIV positive, but the haze of his addictions blinded him. As his health continued to decline, Jesse’s partner urged him to get tested.

When his partner died, Jesse reached his lowest point and entered a residential substance abuse treatment center. The facility required that he take an HIV test, and it was there that he learned that he was HIV positive. Though his housemates at the center tried to calm his fears and provide hope, Jesse saw things very differently; his partner had just died of AIDS and two years prior his older brother died of AIDS—despite taking AZT. With death seemingly imminent, Jesse relapsed, saying “If I’m going to die, I’m going to drug myself out of this world.” For years, he was trapped by his addiction but one day, he looked up, realized how much time had passed, and realized that he hadn’t died. After a few more unsuccessful attempts at sobriety, a new career in HIV services, and a new relationship, Jesse’s life began to change.

His film “The Ceremony,” which documented his decision to have a commitment ceremony with his partner, triggered a desire to come out to his family and the world. As he spoke his truth to his family and friends, he found strength and peace. “That’s the thing about death—you can’t save your face and your ass at the same time. So, I became more concerned with saving my ass by vocalizing who I am and changing the negative thoughts of what a Black gay man with HIV looked like.”

That is when Jesse started speaking about his experience as a Black, gay, HIV positive man to audiences and appeared on several campaigns designed to combat HIV-related stigma. These campaigns also affected Jesse’s view of himself. He says, “I used to disclose to give you a chance to see if you wanted me. Now, I disclose my status up front so that I don’t waste my time with someone who isn’t going to accept all of me.”

While he understands that coming out is a privilege not afforded to everyone, Jesse believes that the fear of rejection can often overshadow the unseen support. “When you make the decision to come out, you have to be ready to expect that everyone isn’t going to clap for you. But what changed for me is that most people were clapping for me. There were only a few people who weren’t. Before, I focused on the one or two that weren’t, now I focus on the crowd yelling ‘Go Jesse!’”

In telling his story, Jesse strives to be a role model for future generations of Black gay men. “When I was young, I didn’t see anyone who looked like Jesse to make me comfortable. At times, I felt like I didn’t fit into the LGBTQ community or the Black community; I was just lost. There are youth that are looking for a role model like me, and I want to be that to them.”